SOURCE:

Idled U.S. Refineries Not Likely to Come Back Online - IER (instituteforenergyresearch.org)

President Biden wants refineries to produce more gasoline to help lower gasoline prices, but operating refineries are running at full capacity and idled refineries are unlikely to bear the high recommissioning costs to come back on line, according to IHS Markit analysis.

About 375,000 barrels per day of the 1.482 million barrels per day of North American refining capacity shuttered since June 2019 may be eligible for restart. President Biden could make it easier for these plants to retool if he genuinely wanted them back online, but he has taken no positive action to back up his repeated calls for more refining.

Refinery owners will not make the huge investments necessary if they cannot recoup their investment, which is likely to take years. It is unclear what the Biden administration will do in that timeline, but it is unlikely to be beneficial to the domestic petroleum industry since his actions have been to produce abroad, not in the United States, as he travels to other countries to beg for more oil production. While U.S. refineries are seeing strong margins currently, it is unclear how long that will last. Refiners are unlikely to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in recommissioning costs for only one or two years of strong returns, against a backdrop of the Biden administration’s promise to “end fossil fuels.”

Since June 2019, 1.482 million barrels per day of refining capacity has been rationalized in the United States and Canada, of which about 590,000 barrels per day was damaged in storms or refinery incidents and is not eligible for quick restart, and 237,000 barrels per day is being converted to renewable diesel production. Only the 375,000 barrels per day mentioned above is eligible for restart.

U.S. Petroleum Demand and Refinery Input

Gasoline demand is at or slightly above pre-pandemic levels and distillate demand is above pre-pandemic levels. But, refinery capacity is less due to closures and conversions to renewable fuel. While demand for gasoline has returned, the ability to meet it has been reduced — or rationalized — away during the pandemic when the demand and margins were down for domestic refineries. There are few options to improve refinery capacity since it takes years to permit and expand existing facilities and the trend in the industry has been to shut down or convert to renewable diesel which receives large subsidies and higher profits. No completely new refineries have been built since 1977, and in fact, the EPA under Biden has begun to question routine renewals of existing refinery permits. Rather than looking for ways to help refineries add capacity, the aAdministration appears to be searching for excuses to close them.

In the past, the industry would expand existing facilities if demand increased, but if something goes wrong — like an explosion — it results in a bigger hit to the industry’s ability to produce gasoline and diesel. Increasing existing refinery capacity rather than building more refineries creates fragility in the system that would not occur if the exact same refinery capacity was built in different locations. Also, much of U.S. refinery capacity is in the Gulf, which can get hit by hurricanes and which will exacerbate the problem.

During the pandemic, refineries operated less, while others closed down completely — including a refinery in Newfoundland. And before the pandemic, a refinery complex in Philadelphia was beset by a series of fires and explosions, which led to its complete shutdown. This was after attempts to keep it open by the Obama and Trump administrations. By late 2020, it was believed that because of structurally lower demand for fuel due to the COVID lockdowns, idle refineries would convert to being storage facilities as opposed to refining petroleum products.

According to the most recent Energy Information Administration data, U.S. refining capacity is slightly below 18 million barrels per day, while in the months before the pandemic shut down, it was around 19 million barrels per day. Further, less oil is going into U.S. refineries daily: According to the most recent EIA data, 16 million barrels per day of oil are entering U.S. refineries, which is well above the pandemic low of just under 13 million barrels, but a decline from the almost 16.5 million barrels per day in February 2020.

Refineries Abroad

China’s refining capacity is expected to reach 18.81 million barrels per day in 2022, overtaking the United States to become the world’s top refiner, according to China’s CNPC’s Economics & Technology Research Institute. This mirrors the shift to offshoring manufacturing of all kinds from the United States coinciding with the growth of the regulatory state in the United States. The Institute expects China’s refining capacity to increase to 20 million barrels per day by 2025. Despite the high refining capacity, utilization rates are low as China has had several COVID lockdowns, which reduced domestic demand. About a third of China’s refining capacity is currently idled. While China could export more, it has cut export quotas because its refining sector is set up mainly to serve its domestic market. The government controls how much fuel can be sent abroad via a quota system that also applies to privately owned companies. And while China has allowed more shipments at times over the years, it does not want to become a major oil-product exporter. In China, many of the new plants are so-called mega-refineries, which have the flexibility to produce both fuels and petrochemicals.

China’s big state-owned refiners, which make up around three-quarters of the industry, were running at around 71 percent of capacity earlier in June. The private processors, known as “teapots,” were operating at 64 percent of capacity. Most of the teapots are not allowed to export any fuel. Last year, China exported around 1.21 million barrels a day of fuel oil, diesel, gasoline and jet fuel –about 7 percent of its total refining capacity at the end of 2020. This year, rather than allow more shipments as local demand drops, it is exporting less. Only 17.5 million tons of fuel export quotas have been allocated so far, compared with 29.5 million tons at the same point last year. Diesel shipments dropped to the lowest level in seven years in May.

New refining capacity has also been added in the Middle East, but exports from there are also limited as well as Russian exports following its invasion of Ukraine.

Conclusion

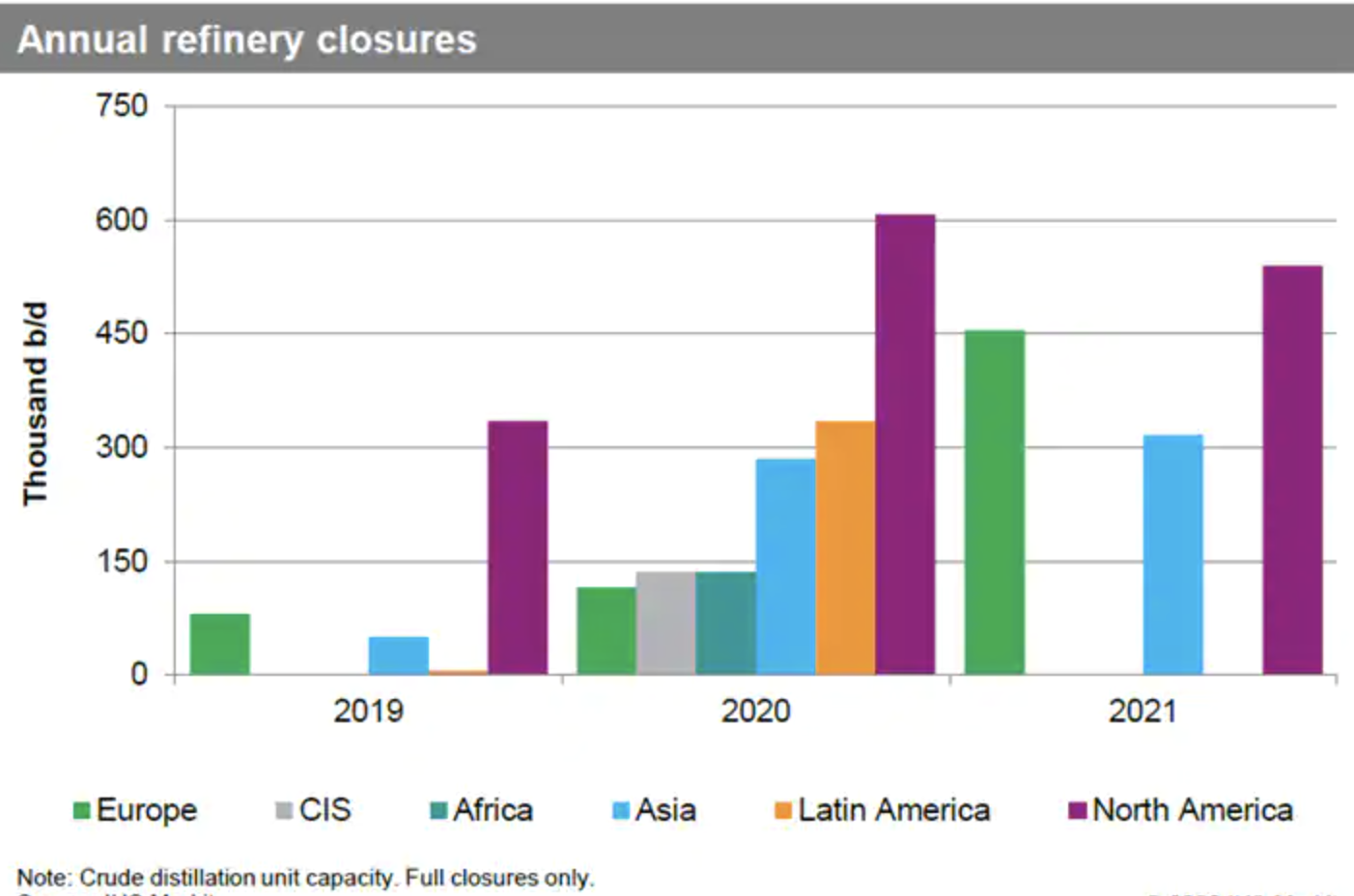

The contrast between China and the United States – where refineries in some areas are running at close to full capacity – reflects a shift in the industry over the last few years. European and North American plants have been shutting down, a trend that was accelerated by COVID-19, while most new facilities are being built in the developing world, particularly Asia and the Middle East. Regulation and government policy outlooks also affect this trend. As the western world is shuttering refining capacity to meet climate change goals, China and other developing countries are seemingly ignoring the goals that they have set up. This means Western countries are increasing the cost of living for their constituents in the name of climate change while countries like China and India are making sure that they have adequate capacity to improve the lifestyle of their inhabitants and the energy security of their nations. In the United States, the Biden administration is calling for more refined products publicly, while its actions all point towards limiting or reducing refining capacity. Americans are seeing the results of these policies each time they buy something made more expensive by increased energy costs.