SOURCE:

Peer review: the seal of quality? (substack.com)

How peer review is touted as the mark of scientific scrutiny but evidence of its effects are lacking. Its use as an insurance policy by editors has allowed poor science and censorship to proliferate

In the early 1990s, an extraordinary mixed group of impressive journal editors, researchers, writers and academics came together to investigate all aspects of editorial peer review.

Grounded on early international congresses of peer review, the group asked itself four key questions: What is (editorial) peer review? What are the aims of peer review? Does it work, and what are the unintended consequences?

A patient (the submitted manuscript) would be assessed by a generalist physician (editor). If the editor did not know quite what to make of the patient's ailments (in this case, the manuscript), specialists would be called in (e.g. a statistician, an economist, a consultant or a researcher in the speciality or topic) and would reach a verdict in the consultation.

One of the fundamental aspects of research is the slow progressive build-up of knowledge, the formulation of theories and their testing, followed by confirmation or rejection of the approach. It is a far cry from the media’s reporting of medical breakthroughs that jump from one miraculous discovery to the next.

The group made progress on process transparency. Guidelines for reporting and peer reviewing were its main products in an age where a civilised discussion was still possible. Peer review should be learned, multidisciplinary and transparent. The anonymity of authors, editors or reviewers would be frowned upon; making remarks about other people’s work and ultimately influencing its fate under the cloak of anonymity is a “licence to kill”.

However, as biomedical publishing became more of a business and public health ethics got progressively diluted, the peer review research impetus diverted to answering less essential questions, such as whether blinding reviewers and authors affect the outcome. Richard Smith, ex-editor of the BMJ, referred to the business of academic publishing: as “a catastrophe”, pointing out that journal ‘profit margins are 30–40%, higher than almost any other business’.

The four key questions have so far been ignored. Publishers use peer review as a mark of quality or reliability despite not knowing what either of those terms means because questions about what peer review is and its aims have not yet been formulated, debated and answered. Peer review has become the Teflon body armour of editors, authors and journalists: ah, it’s passed peer review, so the paper must be robust, valid and accurate!

However, our experience is that increasingly journals (especially the big business ones) refuse to be accountable for the poor quality research, biased presentations and untruths they publish.

The reality is that there is no empirical evidence that peer review makes any difference to the end product. Not because it does not work but because it has never been tested, and its objectives are unclear, undefined and not widely agreed upon.

As late as Sept 2022, Daniel Dunleavy, a social scientist, lamented the “black box” nature of editorial peer review and the lack of progress in its development.

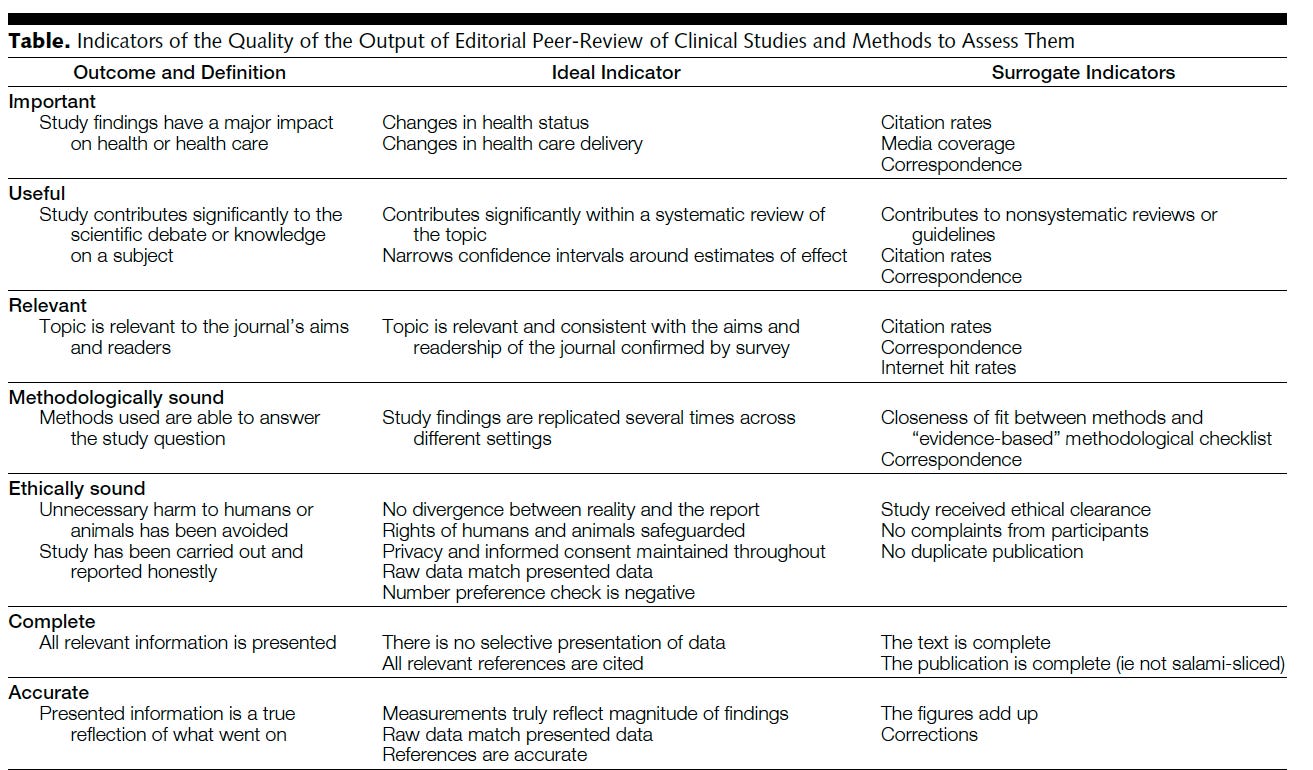

In 2002, in JAMA, we published the table below assuming that effective editorial peer review was the process by which important, useful, relevant, methodologically and ethically sound, complete and accurate manuscripts were correctly identified and separated from those less so. Each of the attributes was given a definition and a set of indicators in a sliding order of surrogacy or indirectness.

So, for example, high citation rates may indeed be associated with importance but quite often with infamy when a study is cited as a negative example.

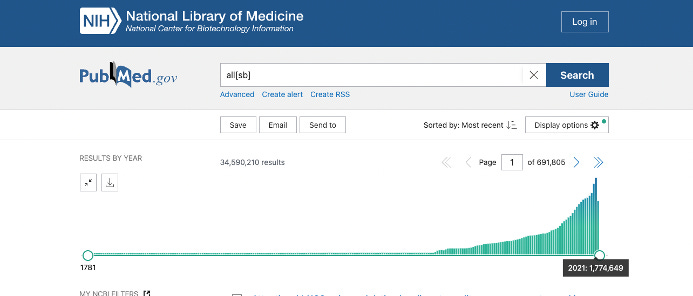

As with many examples, complete reporting is almost never achieved. The real successful outcome would be a study with findings that change healthcare for the better. In the fourth instalment of the Transmission Riddle, the reality is the opposite. There are 34.5 Million articles on PubMed where the biomedical literature is indexed, 1.77 Million journal articles are published each year, and the number is increasing. How many make a difference to patient care?

Editorial peer review can probably help improve manuscripts. In the last two decades, nothing has changed to improve peer review. As journals have become more business-like and the number of articles increased, the impetus to address quality has receded. Worst still, peer review is sometimes used as an instrument of censorship. The proliferation of poor-quality research underpinned by a woeful peer review process perpetuates the massive waste in research and a lack of progress. Consequently, patient care is much worse, while journal numbers increase along with their profits.

References

JEFFERSON TO, ALDERSON P, DAVIDOFF F, WAGER E. Effects of editorial peer review: a systematic review. JAMA 2002; 287:2784-2786.

JEFFERSON TO, WAGER E, DAVIDOFF F. Measuring the quality of editorial peer review. JAMA 2002; 287:2786-2790.